Black Tudors and The Haberdashers' Company |

|||||||||

In her 2017 book Black Tudors: The Untold Story Miranda Kaufmann has written a seminal work which challenges the idea that the horrors of late 17th and 18th Century slavery marked the beginning of Africans’ presence in England, exploitation and discrimination their only experience. The book takes the form of ten vivid and wide-ranging true-life stories, sprinkled with dramatic vignettes and specific details that bring each character to life. |

A wealthy Moor |

Africans were already known to have been living in Roman Britain as soldiers, slaves or even free men and women. Kaufmann shows that, by Tudor times, some were also present at the royal courts of Henry VII, Henry VIII, Elizabeth I and James I, and in even the households of courtiers like Sir Walter Raleigh and William Cecil. It is clear that real change came in William Shakespeare himself wrote several black parts - indeed, two of his greatest characters are black - and the fact that he put them into mainstream entertainment reflects the fact that they were a significant element in the population of London. Their numbers ran to many hundreds, probably more, and they were employed widely, in roles such as domestic servants, professional businessmen, musicians, dancers and entertainers. And to be clear: they were not slaves. Indeed in English law, it was not possible for anyone to be a slave in England itself (although that principle had to be re-stated in the anti-slave trade court cases of the late 18th Century because, as we know, this legal principle was certainly not adhered to in the West Indian Colonies). But in Elizabeth's reign, the black people of London actually were free; some, both men and women, married native English people. Some were given costly, high status, Christian funerals, with bearers and fine black cloth, a mark of the esteem in which they were held by employers, neighbours and fellow workers. In 1597, for example, Mary Fillis, a 20-year old black woman, had, for a long while, been the servant of a widow called Barker in Mark Lane in the City of London. She was the daughter of a Moorish shovel-maker and basket-maker and had been in England 13 or 14 years. Never christened, she became the servant of Millicent Porter, a seamstress living in East Smithfield, and now "taking some howld of faith in Jesus Chryst, was desyrous to becom a Christian, Wherefore shee made sute by hir said mistres to have some conference with the Curat". Examined in her faith by the vicar of St Botolph's, and "answering him verie Christian lyke", she did her catechisms, said the Lord's Prayer, and was baptised on Friday 3 June 1597 in front of the congregation. Among her witnesses was a group of five women, mostly wives of leading parishioners. Now a "lyvely member" of the church in Aldgate, there is no question from this description but that Mary belonged to a community with many friends and supporters |

|

Kaufmann's book also shows us that black Tudors lived and worked at many levels of society, often away from the sophistication and patronage of court life. For example, a West African man called Dederi Jaquoah, who spent two years living with an English merchant, and became a sailor who circumnavigated half the globe with Sir Francis Drake. And the wonderfully named Reasonable Blackman, a Southwark silk weaver whose silk products could easily have been traded in the City of London by members of the Haberdashers' Company, amongst others. Indeed as Kaufmann points out, Reasonable Blackman was not the only independent African businessman who was working in the cloth industry of Tudor London. Some thirty years earlier, in the reign of Queen Mary, Elizabeth's older, Catholic half-sister, 'there was a Negro [who] made fine spanish needles in Cheapside [the heart of the Mercery where Haberdashers had many shops that sold needles] but would never teach his Art to any [as it was a trade secret only he knew]'. Like silk weaving, 'Spanish needles', which were fine sewing needles made of steel, were new to England at that time |

John Blanke Trumpeter for Henry VII & VIII |

|

A reference to this innovative African needle-maker can actually be found in the 1780 Arms of the Worshipful Company of Needlemakers. It shows a bust of a Negro in profile with a red and silver wreath about his head, silver on his shoulders and a pearl earring. This is an allusion to the black man in Cheapside who first brought the art of steel needle-making to England. |

Needleworkers Arms in Use 1780 - 1915 |

|

Despite Kaufmann’s research, it is hard not to think that black people were considered as somewhat exotic figures in Tudor England. She observes, “We need to return to England as it was at the time, an island nation on the edge of Europe with not much power, a struggling Protestant nation in perpetual danger of being invaded by Spain and being wiped out. It’s about going back to before the English got involved in slave trading, before they had major colonies. The English colonial project only really gets going in the middle of the 17th century.” That said, she does leave a stark question hanging in the air: “How did we go from this period of relative acceptance to becoming the biggest slave trading nation in Europe?” In fact Black Tudors were socially no worse off than white ones. At a basic level, they were acknowledged as citizens rather than treated as outcasts. She observes, “It’s enormously significant, given how important religion was, that Africans were being baptised and married and buried within church life. It’s a really significant form of acceptance, particularly the baptism ritual, which states that ‘through baptism you are grafted into the community of God’s holy church’, in which we are all one body.” Kaufmann laments the scarcity of complete historical evidence for black lives in the Tudor period: “I wish they had kept diaries or preserved letters. Much as I’ve pieced together these lives, they’re not satisfying biographies where we know everything – more often, they are snapshots of moments.” Dr David BartleCompany Archivist |

Charles Pearson, Haberdasher |

With the opening of the extension to the Northern Line via Nine Elms and Battersea Power Station, as two new stations, it seems timely to recall the origins of the entire Underground and its connection to one of the Haberdashers’ Company Liverymen.

|

|

Charles Pearson (1793 – 1862), Haberdasher was a British lawyer and politician. He was solicitor to the City of London, a reforming campaigner, and briefly Member of Parliament for Lambeth. He was born at 25 Clement's Lane in the City of London, the son of Thomas Pearson, Haberdasher, an upholsterer and feather merchant and his wife Sarah. After education in Eastbourne, in 1808 he was apprenticed to his father but studied law and qualified as a solicitor in 1816. In 1817 he became a Freeman of the Haberdashers’ Company. From 1845 Charles began to promote the idea of an underground railway through the Fleet Valley to Farringdon, the first man of influence in the City to do so. This idea failed, as did his proposal for central station at Farringdon in 1846. But by 1854 The Royal Commission on Metropolitan Railway Termini had recommended a line between the Docks and the Post Office HQ at St Martin's Le Grand and there was also a successful private bill for the Metropolitan Railway Company for a line between Praed Street in Paddington and Farringdon. Although he only held 50 Shares in the Metropolitan Railway Company, Charles continued to promote the project over the next few years and used his influence to help the railway company raise the £1M of capital needed for the construction of the line. He persuaded the City of London to invest on the basis that the underground railway would alleviate the City's congestion problems. So it was that by 1860, the funds had been collected and the final route decided. Work on the railway started; taking less than three years to excavate through some of the worst slums of Victorian London and under some of the busiest streets. Charles Pearson died of dropsy on 14 September 1862 and did not live to see the opening of the Metropolitan Railway on 10 January 1863. He had refused the offer of a reward from the grateful Metropolitan Railway Company, but, shortly after the railway's opening, his widow was granted an annuity of £250 per year. He was buried at West Norwood Cemetery on 23 September 1862.

|

|

| Constructing the Metropolitan Line at Kings Cross, 1861 |

Dr David BartleThe Archivist

|

Beaver Hats |

and the Arnold family, Haberdashers |

In my article in the last Company magazine I discussed the Daniel family and specifically mentioned William Daniel who is described in London Bridge records of the 1620s as ‘a ‘beavermaker’ or maker of fashionable beaver skin hats. As this fashion was so popular from the 16th Century in London and elsewhere it seemed a good time to consider the topic of the trade in beaver skin hats more fully and to bring in yet another Company member’s link to that trade. |

|

Among the most curious archives held at Lambeth Palace Library are the Bacon Papers. They include bills for beaver hats of the highest quality, supplied between 1594 and 1597 to Anthony Bacon, elder brother of Sir Francis Bacon, the philosopher and politician. These bills include items for trimming and lining two old beaver hats belonging to a young manservant - who was apparently Bacon’s lover. These hats came from two haberdashers, a father and son called Richard and Samuel Arnold: or rather, ‘le Chapelier Mr. Arnould’, as the latter liked to be known. It appears that Anthony Bacon never paid his bills on time, and so the Arnolds kept sending him new invoices for silk, velvet, and taffeta nightcaps, as well as for beaver hats and their repair. Because they sent so many bills, these Bacon Papers help us to understand the practice of the early beaver hat trade clearly. In all Anthony Bacon bought fourteen hats from the Arnolds, five made from beaver felt and nine made from wool, but the beaver hats were by far the more expensive. They cost five times as much as the inferior woollen version. Even the cheapest of Bacon’s beaver hats carried a price tag of thirty-five shillings (around £500 in today’s money). It was big, black, and lined with taffeta. Above the brim, it had a hatband made of “Sypres,” meaning a transparent, gauzy crepe silk, imported from the Middle East via the island of that name – ‘Cyprus’. A forty-two-shilling hat came with a finer surface, and an even more extravagant interior: “a blacke smoth bever lyned with velvet with a duble Sypres.” But the most expensive hat the Arnold’s sold cost forty-six shillings, and sat very grandly on the wearer’s head, because it was black, smooth, and “lynd with tafyta and quylted in the head and a three pleat Sypres band therto.” When beaver hats wore out through use, or fashions changed, they could be repaired, remodelled, re-dyed, and lined with new material. The cost of doing this varied from as little as one shilling (“for mendinge an old bever”) to as much as sixteen shillings, for a hat dyed and lined with taffeta and velvet. |

| Queen Anne of Denmark in a splendid, plumed example of beaver hat |

|

Because it could be reconditioned, and its shape or trimmings modified, the beaver hat became a flexible marker of one’s social status. Among the Bacon invoices, the cheaper alterations had been applied to the hats worn by Bacon’s young friend, while the more expensive alterations were for Bacon’s own exclusive hats. In an age obsessed with rank and degree, the beaver hat’s adaptability gave it a special appeal. Soon hat makers found a host of ways to give each hat even more character, with gold and silver wire and silk in many different shades. A dull old hat with obsolete trimmings would tarnish its owner’s status, while commissioning a new beaver hat would elevate it. The same prestige applied to the men who sold the hats, and in the undertaking all of this, the Arnolds were far more important socially than mere artisan haberdashers. The wares of Beaver hat makers were for prosperous people, and the Arnold family lived for four decades in the wealthiest wards of the City, West of St. Paul’s Cathedral, where they ranked among the highest taxpayers and were near neighbours of William Shakespeare when he lodged there. The Arnolds were aristocrats of retail commerce and they embodied the links between exploration, luxury, and their fervent Protestant faith. Later historians have often portrayed Puritan merchants as troubled people, afflicted by an inner conflict between their religion and the stress of lucrative commerce. This does not seem to have worried men such as the Arnolds. As senior Haberdashers, they supported Puritan clergymen, such as John Downam, a protestant divine who acted as the Haberdashers’ Company’s spiritual adviser and had written several devotional books that William Brewster leader of the 1620 Mayflower Voyage community in America collected: Brewster owned seven copies of Downam’s sermons and manuals of prayer in the Plimoth Plantation. Yet at the same time, they sold large quantities of wildly expensive beaver skin hats with no sign of unease! At his death in 1618, the “chapelier” Samuel Arnold left five pounds to “my loving ffrend Mr. Samuell Purchas, Minnister of the parish at St. Martens at Ludgate.” Purchas was cleric of many talents and the editor of 'Purchas His Pilgrimes', a sprawling compendium of seamen’s and travellers’ tales from all parts of the world. First published in 1617, it too was used by the Mayflower Pilgrims as it contained a sea captain’s description of the neighbourhood of New Plymouth where they were headed, written only a short while before the Mayflower’s voyage.

|

|

Versatile, sensuous, durable, but chic, visibly expensive but open to subtle reinvention, the flexibility of the beaver hat became a Jacobean version of the Peacock Revolution style designed in the 1960s. Worn by women as well as men — the portrait of Anne of Denmark, King James’s queen, shows her wearing a splendid plumed example — it retained the status of a fashion classic for nearly two centuries. It did so because evolving social aspirations of that time found an outlet by way of the special qualities of the Beaver’s fur. |

Dr David BartleThe Archivist

|

The Old London Bridge |

and the Haberdashers' Company |

The medieval Old London Bridge stood from 1209 until it was finally demolished in 1831. It was one of Europe’s largest and most spectacular inhabited bridges. For most of that time it was a hub for City of London traders, standing as it did as the sole crossing from Southwark into the City. This primary role made it very busy indeed and a captive market for the traders who lived and worked on it. |

|

| London Bridge 13th & 14th Century Appearance |

|

During the first lockdown, I was asked as Company Archivist by Channel Five if I would provide an interview for a new programme they had commissioned on London’s Greatest Bridges, in particular to appear in the first episode about Old London Bridge. This was because a great many of the traders on the bridge throughout its history were haberdashers and also most were members of the Worshipful Company of Haberdashers. In 1478 there were some 23 haberdasher traders who were our members living and working on the bridge and a similar number throughout the 16th Century, and there were still as many as 13 members living and trading on the bridge as late as 1633. One family was used in the programme to exemplify this over several generations, the Daniel family. Their family fortunes trading on the bridge went between 1600 to c.1685 - which includes the most dramatic property developments that occurred there. Lionel Daniel was a haberdasher of hats in his own house on the bridge from 1625 or earlier until it was burnt down in 1633. His son William had been apprenticed to him in 1616 and in 1624 had set up himself as a haberdasher at a separate address on the bridge; later he is described in a trade document as a ’beavermaker‘, in other words a maker of fashionable beaver skin hats. He added a second house on the bridge to his property in 1645 and had largely rebuilt the combined substantial property by 1650. He was a Warden of the Haberdashers’ Company twice in 1661 and 1666, was a Common Councilman of the City on several occasions and was elected an Alderman of Farringdon Within Ward in 1670, though as he was a Religious Dissenter he was unable to serve, so he paid a fine instead. From 1641 until his death in 1678 he also had a house in Clapham, as well as properties in various parts of London, Southwark and Essex. He and his wife are the only bridge inhabitants of whom portraits have been located (reproduced here). |

|

| William and Mary Daniel, circa 1670 |

|

William’s son Peter Daniel was a merchant, and was living in one of the family owned bridge houses by 1676. In 1678 his household on the bridge consisted of himself, his wife Elizabeth, five children, an apprentice, a journeyman, five maidservants and one manservant (the only one to be found on the bridge). In contrast to his father he was a Tory. He was an Alderman from 1682 to his death in 1700, was twice Master of the Haberdashers’ Company in 1683 and 1689, was knighted in 1684, was an MP in 1685–87 and was one of the City grandees to whom Charles II committed the control of the City’s estate in the 1680s. He was heavily involved in the widening of the bridge’s roadway in the 1680s, being on the committee appointed to implement it and acquiring and then selling leases at the northern end. He sold the leases of his own properties and moved away when it was rebuilt in the mid-1680s. Peter Daniel was an unusual figure in the bridge’s history. Many of the bridge’s residents were wealthy, but they were retailers and wholesalers rather than merchants, and virtually none apart from Peter Daniel were to reach the high City rank of Alderman or Master of one of the Great Twelve Livery Companies. Our Company archives record that at Court of Assistants dated March 1683, some of the Company’s silver plate was to be sent to Sheriff Daniell at his City address: But, as mentioned earlier, the association of the haberdashery trade and the bridge is one that goes right back to the earliest days of its existence. Along with Cheapside, the Old London Bridge was the part of the City that even witnessed the birth and growth of the haberdashery trade in the early 14th Century. The numbers of our members on the bridge grew substantially through the 15th and 16th Centuries. And in recognition of this, in 1592 the Clerk of the Haberdashers’ Company, Lambert Osbolston (1580-1602), was appointed to be the collector of wheelage on London Bridge, one of the City’s most lucrative tolls. Given the high volume of carts and other traffic that daily crossed the bridge and back from Southwark, the economic importance of this appointment would have made the appointment a great civic honour. Finally there is a record of the inhabitants of the bridge that concerns one of our old members. It is touching and very evocative of what life was like living on it: |

|

| London Bridge 16th Century (Museum of London Model) |

Dr David BartleThe Archivist |

|

|

The Great Plague and Fire of London1665 -1666The Great Plague that began in 1665 killed an estimated 100,000 people in London, almost a quarter of the city’s population. |

|

In 1664 Sir John Lawrence had been elected Lord Mayor of London and at the same time was again elected Master of the Haberdashers’ Company. It is also known that Sir John as Lord Mayor was one of few ‘great men’ of the city to remain in London at the time. According to the Venetian ambassador, he had a glass case made for himself in his house in St Helen’s Place, from within which he supervised business and received visitors. British History Online, citing a contemporary account, says: ‘Amidst the factions and the vulgar citizens of this reign, Sir John Lawrence, Mayor in 1664-5, stands out a burning and a shining light. When the dreadful plague was mowing down the terrified people of London in great swathes, this brave man, instead of flying quietly, remained at his house in St. Helen’s, Bishopsgate, enforcing wise regulations for the sufferers, and, what is more, himself seeing them executed. He supported at his own expense during this calamity 40,000 discharged and abandoned servants.’ |

|

|

Then - as the plague eased - on 2nd September 1666 and for five days that ‘most horrid malicious bloody flame’ known as the Great Fire of London destroyed much of the old City. Assembling on the 2nd October at Cook’s Hall in Aldersgate Street, the Assistants of the Haberdashers’ Company contemplated the wrath of God. They declared themselves: ‘… very sensible of the great Displeasure of Almighty God which hath been lately manifested against this City in the late dreadful and lamentable fire, and how deeply with the rest of the City this Company and members of it do suffer thereby (their Hall and most of their houses in London being consumed)’. Dr David BartleThe Archivist

|

The Lord Mayor's Show 1632‘London’s fountain of arts and sciences’ was the Pageant in 1632 held in honour of Sir Nicholas Rainton, Haberdasher Lord Mayor: ‘Exprest in sundry triumphs, pageants, and showes, at the initiation of the Right Honorable Nicholas Raynton into the Maiorty of the famous and farre renowned city London. All the charge and expence of the laborious proiects both by water and land, being the sole undertaking of the Right Worshipfull Company of the Haberdashers.’ Written by Thomas Haywood. What follows is a summary of this Pageant’s dramatisation: |

|

Style of a Lord Mayor, c. 1630 |

|

SIR NICHOLAS: What a day of memories this has been... Yes, what wonderful pomp and pageant I have been After swearing my allegiance at Westminster, more wonders were SIR NICHOLAS: Next, as our journey progressed, we were met by PERSEUS: |

SIR NICHOLAS; Arrayed around the fountain model were twelve men dressed in the colours of the twelve guilds, of which mine, the Haberdashers, is one. From the fountain’s heart, another man spoke his message to me... ‘FOUNTAIN’: |

Dr David BartleThe Archivist |

|

|

Frosty-Faced FogoA Hard-Hitting Non-Conformist at the HallDiscoveries about the past of the Company, its Hall and members can sometimes occur as the result of enquiries to search our archives. So it was with the curious story of one John ‘Frosty Faced’ Fogo. |

|

|

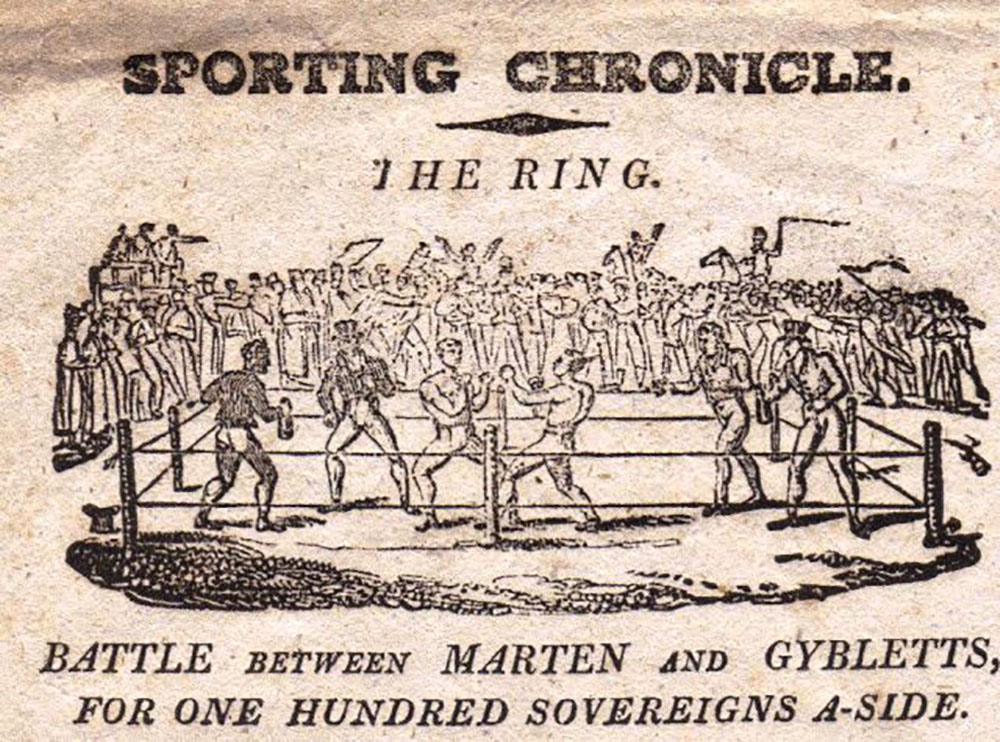

A descendant of this colourfully named man contacted me some months ago to find out more about his family who lived near our Hall in the City of London. She told me that Frosty Faced Fogo (as he was generally known to all in his lifetime) had regularly attended the chapel attached to our Hall during the early 1800s. Now our second Hall, which opened following the Great Fire of London in 1671, had included from its initial construction a Meeting House (or Non-Conformist Chapel) as a discrete building at the back of the Hall premises. Access to this ‘chapel’ was both from Staining Lane outside and internally via the Court Room. So it was that for the local Londoners who attended our ‘chapel’ to hear the word of the Lord, it also acted as the place to record marriages and the birth and baptism of their children. The surviving records of such baptisms now in the International Genealogical Index under the entry ‘Independent Chapel in Haberdashers’ Hall’ cover the years 1785 to 1825. It was thus to these records that I turned and discovered that John ‘Frosty Faced’ Fogo and his wife Ann baptised three children in our ‘chapel’: John Fogo on 31st March 1816 In return for supplying this information, the enquirer was kind enough to share a bit more information about her ancestor which I was then able to follow up in more detail. Here then is all that is known about Frosty Faced Fogo who was once a congregational member of our ‘chapel’, indeed the only one currently known about in any detail. Perhaps unsurprisingly John Fogo was nicknamed Frosty Faced because of his severely smallpox-scarred face, which gave him a very startling and memorable frost-bitten like appearance. A shoemaker by trade he became a founding member of the renowned Daffy Club, which was a group of heavy-drinking boxing enthusiasts who used to meet at The Castle Tavern in Holborn. Records have recently been found in Hungerford, Berkshire of a headline bare-knuckle prize fight in 1827 where one of its main promoters is named to have been Frosty Faced Fogo. A newspaper report makes it clear that the prize fight had to take place outside London, it had originally been scheduled for Marlborough, but this had been prevented by the “beaks”. In the event, even the Hungerford contest was broken up by the arrival of four constables, but not before three vicious rounds had taken place and quite a lot of physical damage had occurred to both combatants. So well-known in such boxing circles was Frosty Faced Fogo in London that he is even mentioned in passing by Charles Dickens in his novel ‘The Mystery of Edwin Drood’ with the words ‘...in days of yore [Fogo] superintended the formation of the magic circle with the ropes and stakes’. Contemporary records even show that he was sufficiently notorious to have gained the acquaintance of the Prince Regent! |

|

|

Seemingly a man of many parts, he was known as a poet, indeed sometimes referred to as being “The Poet Laureate of the Boxing Ring”. This verse written by Frosty Faced Fogo is called ‘Morning Reflections’ and appeared in the Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette on 9th March 1839. Just two weeks after this poem was published, Frosty Faced Fogo died: Who has not known that painful hour, Oh! how we execrate the beer, My memory is quite confus’d! Night after night to keep it up Left by my comrade in the lurch, Moral Then lads, of getting drunk beware, |

Dr David BartleThe Archivist |

Gilbert Shakespeare in LondonThe Bard’s Brother and a Haberdasher by TradeThe English poet, playwright and actor William Shakespeare is now widely regarded as both the greatest playwright in the English language, perhaps the world’s pre-eminent dramatist. William was born into an affluent Guild family of Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564. He was one of eight children born to his father John (a Glover or glove-maker by trade and a town Alderman) and amongst these siblings was a younger brother Gilbert, born on 13th October 1566.

|

|

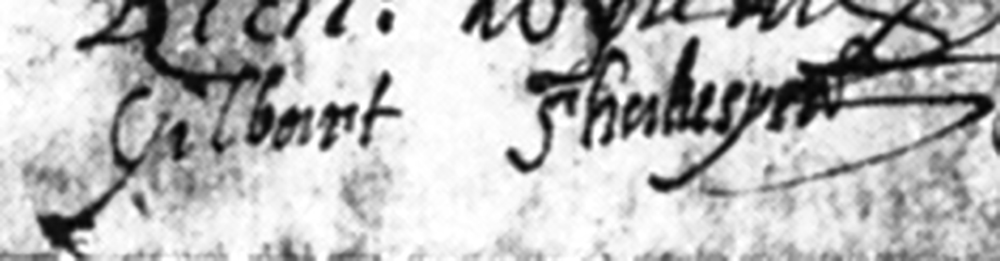

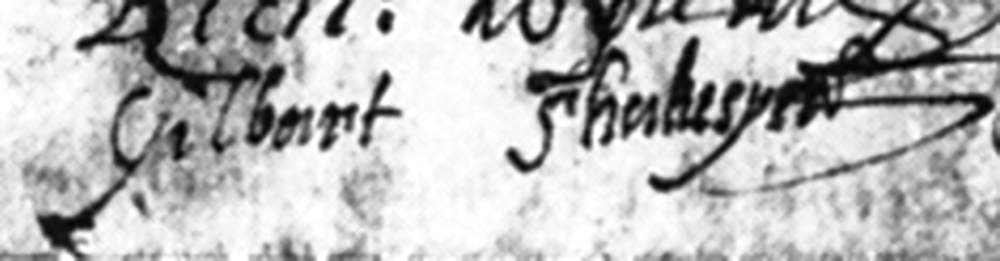

|

Gilbert Shakespeare was the closest boy in age to his brother William and in their early years the two boys must have shared much in common in their experience of life. In the early 1570s records in Stratford show that Gilbert contracted, but luckily survived, the plague. It is also known after this that William attended the grammar school in Stratford and it is almost certain that Gilbert did so too. Similarly both must have seen civic life in Stratford through their father’s aldermanic town role and no doubt they saw a lot of his trade activity as a Glover and those of his many town contacts in their allied trades (perhaps even including haberdashers). Some of these tradespeople probably are reflected later in William Shakespeare’s plays - such as ‘A Midsummer Nights’ Dream’. Then suddenly in the late 1590s and aged nearly 30 years of age, Gilbert Shakespeare is to be found working in London. Specifically this detail is known from a record of the Queen’s Bench in London dated 1597 when he stood bail for one William Sampson (a clockmaker from Stratford-upon-Avon). It is in this record that Gilbert’s trade is stated to be ‘a haberdasher of St Bride’s Parish’. This fact that this is given to be his occupation is of great interest as it shows that Gilbert was in some way involved with the Haberdashers’ Company, or if not that, at least the trade which our Company tightly controlled within the square mile of the City. But before exploring that point further, it is worthwhile considering why Gilbert might have been able to work in this trade at all. It is in documentary records we find that William Shakespeare is stated suddenly to be in London also in connection to a law case before the Queen’s Bench court at Westminster but in 1588 -89. He is then mentioned again as part of the City theatre scene in 1592. So it is that William was the first of the brothers to move down to London, no doubt as part of his growing ambition to succeed in the world of the London theatre. It is then known from records that it was the youngest child of John Shakespeare, Edmund Shakespeare (b. 1580) who came down after William, most probably in the late 1590s. |

|

Perhaps in fact Gilbert and Edmund both came down to London together following their brother William at that time? If so, they were heading into very different working lives - Edmund was to become an actor (like William himself) and Gilbert was to take up a cloth trade activity. Perhaps this was because of all his sons; it was John’s son Gilbert who was the most inclined or able to take up a trade at least allied to that of a Glover. There is nothing but speculation to suggest that Gilbert learned about glove-making or aspects of retail haberdashery either from his father or from other working experience in Stratford. There is no record to suggest that Gilbert was ever apprenticed to his father as a Glover or to anyone else in Stratford or London in haberdashery or any other similar trade. But it seems very unlikely that Gilbert could have taken up work as a haberdasher of St Brides Parish unless he did have some sort of prior knowledge or experience of the trade. |

|

|

|

Aged nearly 30 years old on his arrival in London, Gilbert would not have been a suitable candidate for apprenticeship by this time. It would have been hard and expensive for him to have joined the Haberdashers’ Company by redemption and set up and run his own business in the City. So it seems most likely that he worked as an assistant to an established haberdashery business that was located in St Brides Parish. For instance there was one such haberdashery business in Fleet Street within St Bride’s Parish known to have been run by one Edward Boyce who became a Freeman of the Haberdashers’ Company in 1581 aged 27 years. In addition to this working life in London, it is also thought that Gilbert paid frequent brief visits back to Stratford, as did his brother William. Recent research at the Guildhall Library has pointed to the likelihood that some sort of informal ‘licensing’ of non-freemen to work in the City of London for an established business was in operation during the 16th Century and perhaps long before. This would have been the precursor to the recorded formal registration process for such ‘licensed working’ that was to become formalised in City licence books from 1750. |

|

|

Records of the Haberdashers’ Company agree with the Guildhall Library that the level of required employees - just in regulated haberdashery outlets and businesses across the City of London for instance - must have far exceeded the number of Company recorded apprentices and freemen available to work there. So there must have been other authorised and experienced labour to draw upon that was not made up of Livery Company members and it is into this sector of ‘haberdashery employment’ that Gilbert would seem to fit. Further to this, we only know that by 1602 and after around 6 years ‘haberdashery work’, Gilbert had abandoned his peripatetic working life in London and returned to live permanently in Stratford-upon-Avon. His untimely death occurred in 1612 aged just 46 years. Edmund died in London in 1607 aged just 27 years and William - who also returned to Stratford - in 1616 aged 52 years. |

|

My thanks to Elizabeth Scudder, Principle Archivist, LMA and Murray Craig, Clerk of the Chamberlain’s Court.

|

John BanksAn Enigmatic Company Benefactor |

|

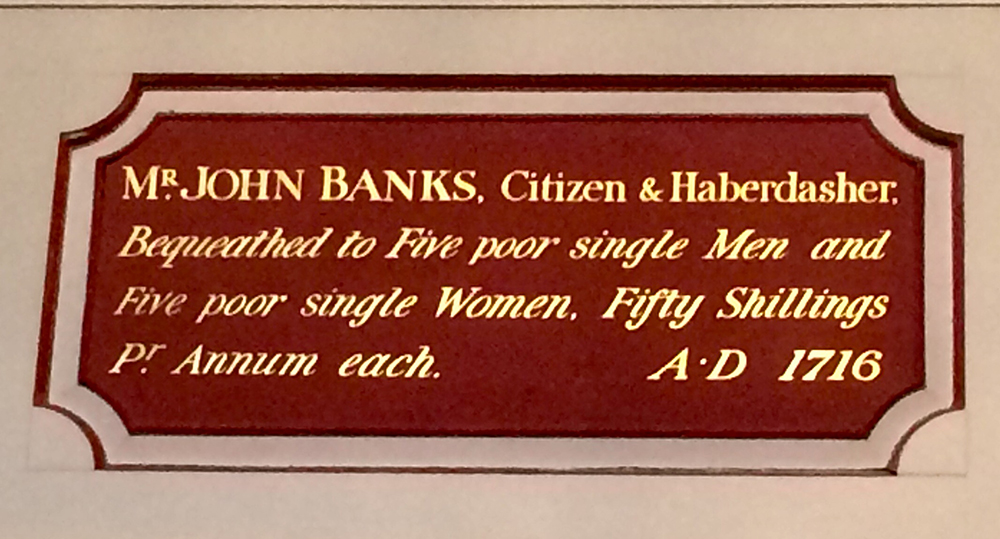

John Banks was born c.1652 and became a Citizen Haberdasher and Mercer (by trade) of the City of London. He was connected with the Levant trade by way of silk dealing. Admitted to the Freedom of the Haberdashers’ Company in 1672, Banks became Master in 1717, and died the following year. All that is known about his family is to be found in his will and the associated tree of beneficiaries that has developed from it. From this document he is known to have had two half-brothers and three half-sisters. It is sadly fair to say that in many ways the life of John Banks remains an enigma to us today. |

|

Banks’s early years occurred in a notable period of turmoil in British history: he was born during the interregnum, just three years after the execution of Charles I. But it was also a time of increasing national prosperity, as foreign trade was growing in importance to this country. In the midst of this growing prosperity, however, there were many poor people applying for relief from the parish, and so it fell to the newly prosperous merchant tradesmen to play a large part in the alleviation of this widespread poverty. In fact merchants and tradesmen were responsible for some 70% of charity and charity endowments in the 17th century. So it was in this context that the hugely successful John Banks decided to set up a Charitable Trust, to be administered by the Master and Wardens of the Haberdashers’ Company, and part of his benefaction was that certain ‘sums should be annually paid, for putting out apprentices, helping to set up in business, or towards the marriage of the descendants of my relations, in such proportions as my Trustees should think fit.’ Thus as succeeding generations claimed their benefits under this bequest, each had to state the basis of their claim and this meant they had to provide documentary evidence of their parentage etc, to the trustees of the charity and how it linked back to one of the half-siblings of John Banks. This evidence may have taken the form of sworn statements or, after 1837, registration certificates. These ‘genealogical’ details were meticulously recorded by the Haberdashers' Company because in John Banks’s will, the Master, Wardens and twelve Assistants were appointed as his Trustees (this Trusteeship document has recently been discovered and now hangs in the display room of the Hall). In return for this work he left money to provide the Court with dinner after their half-yearly Trustee meetings and it is this act that is the origin of today’s annual banquet in his honour. The noting of the relationships of the various claimants has today resulted in a large `family tree' of claimants, which stretches back to 1716. The cash benefaction relating to kin was wound up only some years ago, due to the ‘too numerous applications and much dwindling sums.’ In its course it had been in existence for approximately 260 years. Meanwhile many other charitable payments are included in Banks Trust, making funds available to poor and elderly men and women, inhabitants of parishes such as Battersea, St Benet Paul's Wharf and St Mary Overy in addition to several annuities to specific relatives; all together the bequests totalled £912. The poor people were selected by the Company acting as trustees as being suitable persons to benefit from charity; many of them were of the yeomanry, or widows of freemen. |

|

|

To provide funds for this Charity, John Banks bequeathed his leasehold estate in St. James’ Parish, Westminster along with property in Clerkenwell to the Master and Wardens of the Haberdashers’ Company and their successors, upon trust, to pay out of the rents and profits and residue of same the sum of £10,000 and interest. This estate originally included 72 houses in Westminster, held by lease under the Crown, and two further freehold houses in Clerkenwell. Banks left instructions that the lease from the Crown was to be renewed upon expiry, but in 1822 the Company were advised by two consultants that the terms of renewal of the lease were `unreasonable' so the lease was not renewed and the 72 houses in Westminster ceased to form part of the charity. One can only guess at the likely value of these properties to the trust had they still been part of its assets. Dr David BartleThe Archivist |

William Hogarth and his Haberdasher Uncle |

|

Researches done by Dr Ian Archer, Liveryman, for the 1991 volume of our Company History showed that one of the areas trading haberdashers of past centuries owned shops in the City was on old London Bridge and its environs.So it was that as late as the 18th Century one Edmund Hogarth (1672-1719), uncle of the famous artist William Hogarth, owned just such a shop. Edmund was in fact a wealthy merchant and also owned a victualler’s business (that may have grown out of a haberdashery shop) at the sign of the Red Cross which was close to London Bridge - on the City side of the river. At the start of his career Edmund had purchased his freedom of the Haberdashers’ Company on 8th February 1705/6 by Redemption and it was soon afterwards it appears that he arrived and set up his business in London. It is most probable that he would have been apprenticed outside London, around 1698. On 12th August 1707 Edmund secured a license to marry Sarah Gambell, thirty years old and a spinster of St Swithin’s parish. His own age at that time is given as thirty-five and this age suggests that either he was apprenticed later than the usual age or could not afford to purchase his freedom of the Haberdashers’ Company for some time after his apprenticeship had ended. When visiting his uncle, the young William Hogarth would have seen the great stone gate at the southern end of the old London Bridge (close by where his uncle Edmund lived and worked) and with it the exhibited heads of traitors and other malefactors would have been clearly visible in all their horror - much replenished as they had been after the Jacobite rebellion of 1715. |

|

William Hogarth had been born in 1697 at Bartholomew Close, Smithfield (close by our present Hall) one of several children to Richard Hogarth who was a poor Latin school teacher and textbook writer, and his wife Anne Gibbons. In his youth William was apprenticed to the engraver Ellis Gamble in Leicester Fields, where he learned to engrave trade cards and similar products. The young William took a lively interest in the street life of London and especially the London fairs (such as Bartholomew’s Fair in Smithfield), and amused himself by sketching the characters he saw. Around this time, his father, who had opened an unsuccessful Latin-speaking coffee house at St John’s Gate in 1703, was imprisoned for debt in Fleet Prison for five years. William was so ashamed of this that he never spoke of his father’s imprisonment. When Edmund died suddenly in 1719 he was aged just 47 years old but it appears he had by then cut his brother Richard’s family, including William, out of his will. As mentioned above Richard Hogarth was William’s impoverished father, he had in fact died in 1718. This hard-heartedness seems to have led the embittered William to recreate his uncle and his City dwelling very unsympathetically in his portrayal of the miserly merchant and his mean (i.e. miserly) quarters in one of his paintings series - ‘Marriage-a-la-Mode 6, The Lady’s Death’ c.1743. Note that old London Bridge can be seen outside the window of what is undoubtedly his uncle Edmund’s house in this picture. The Marriage à-la-mode series of paintings 1743-1745 presents the story of the fashionable marriage of the son of bankrupt Earl Squanderfield to the daughter of a wealthy but miserly City of London merchant (for whom William appears to have had his Haberdasher Uncle Edmund in mind). It all starts with the signing of a marriage contract at the Earl’s luxurious mansion and ends tragically with the murder of the son by his wife’s jealous lover and the subsequent suicide of the daughter in her merchant father’s house in London after her lover is hanged at Tyburn for the murder of her husband (as is depicted in this painting).

|

|

|

|

Source: Records of the parish of St Magnus the Martyr (first noted in Le Hardy’s ‘William Hogarth’; records of the Haberdashers’ Company; Bishop of London’s Register, The Publications of the Harleian Society, 26 1887). Dr David BartleThe Archivist |

Ambrose WittA snaphot of Employment in a Victorian Livery CompanyLate in 1854, Ambrose Witt was appointed Under Beadle/Porter of the Haberdashers’ Company. Astonishingly on 8th September 1856, the Court of Assistants was to receive a letter from him – requesting an immediate increase in his wages! |

|

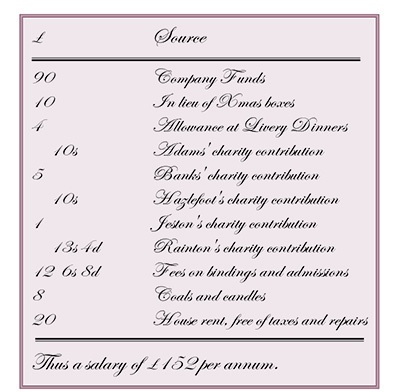

Now it should be noted that Ambrose was initially appointed to the post on a temporary basis. In his application he describes himself as having “done the duties of Porter since the pulling down of the old buildings”. This remark was probably his reference to the 1854-56 substantial redevelopment of our 2nd Hall, which included the addition of an extra floor. In response, the Court decided to set up a special Committee to consider both his request over pay and the terms of establishment of a permanent Under Beadle/Porter post. The Committee reported on 7th October 1856, and in the archives there is a full copy of the Committee’s findings in our Report Book (Vol 9 pp 385-87): The Committee began by looking at the annual earnings of the previous Under Beadle/Porter which had been made up in the following manner

|

|

|

While £100 per annum was now to be paid quarterly by the Company, in addition to this only the combined monies from the charities which came to £7 13s 4d per annum were to be added – making a new total salary of £107 13s 4d. The Committee stipulated there would be a clothing allowance of one ‘dress’ and one ‘undress’ livery “of a plain pattern” with a hat, all to be renewed every year. The Under Beadle/ Porter was to pay his own income tax, and there would be just one calendar months’ notice on each side of intention to terminate employment. But worst of all for Ambrose, the Committee decided that the post was to be thrown open, and a notice of the vacancy was to be pinned up on the board outside the Hall entrance in Gresham Street for the public at large to see. The notice made clear that it was not necessary for the successful applicant to be a Freeman of the Haberdashers’ Company (which Ambrose was not), but that preference would be given to a married Freeman of the City, who must not be over 40 years old. The Committee also outlined the duties, which were:

The hours were to be 7am-6pm, “sufficient time to be allowed him for Dinner”! The Committee’s report was accepted at the Court of Assistants held on 13th October 1856, and by 11th November the Committee had identified 3 candidates for election by the Assistants:

A suddenly proposed motion to postpone the election until after the Livery dinners was lost by 15 votes to 6, and then… Ambrose Witt was narrowly elected to the post which he had previously been filling on a temporary basis. The Court of Assistants held on 8th December records the receipt of his letter of thanks for his appointment, but (as is sadly usual in such fascinating cases) the minutes do not give us the text of this letter. Then nine years later, on 6th June 1865, the Court of Wardens considered arrangements to be made “upon the Under Beadle/Porter’s ‘going into residence’ in recently vacated accommodation in the Hall. It was stated that Ambrose had to “provide himself with House Room, and Coals and Candles”, and the annual value of the house was assessed at £20 free of taxes and repairs, while the value of coals and candles was thought to be £8. As a result of getting this new benefit, the Court of Wardens recommended Ambrose take a cut in pay - to £80 plus the £7 13s 4d from the charities. And if in agreement, that he be allowed to take up the apartment in Haberdashers’ Hall, Staining Lane. The Company somewhat relented and finally offered to pay rates, taxes and repairs on his behalf, and to supply coals and candles. Then on 7th May 1872, the Court of Wardens finally seemed to respond to Ambrose’s original request for a wage rise in 1856 by awarding him an extra £10 pa, but on 17th September his duties were augmented: “The Porter and his Wife shall have the charge under the Beadle’s directions of all the rest of the building, comprizing the great Hall and the entire of the apartments, entrances and Staircases on the ground and basement floors, also of the lavatories and staircases leading to them, the whole of which are to be kept by them constantly clean, and in good condition.This will not include Mr Curtis’s offices, and the Staircase leading to them”. We next hear of Ambrose on 1st November 1875 when the Court of Wardens read an application for financial assistance from him “on account of his extra expenses through long illness in his Family”, in response they granted him £20. After that, nothing more is heard until a Court of Assistants meeting on 8th June 1896, when an unspecified letter sent by him was referred to the Officers’ and Clerk’s Committee. We can infer that this was his letter of resignation, as - assuming his age to be accurately given on his appointment - he would have been 72 by then. On 12th October Ambrose is described in retirement as “late our Under Beadle” and he was elected to receive 2 pensions of £50 pa each out of the Aske charity. Finally we read that at a Special Court of Wardens held on 9th July 1896, Ambrose was admitted to the Freedom of the Company by Redemption and his last address is given – in a Company almshouse at 3 Staining Lane. Dr David BartleThe Archivist |